A Land Born from Ancient Rock

The Black Hills are not just mountains — they’re some of the

oldest exposed rocks in North America. Long before the Great Plains stretched around them, this region was already writing its story in stone.

Rocks Nearly Two Billion Years Old

At the core of the Black Hills are

Precambrian rocks, formed about 1.8 billion years ago. These include granite, schist, and slate — the very building blocks of Earth’s earliest continents. For perspective, that’s nearly half the age of the entire planet.

When you stand among the

granite spires of the Needles Highway or run your hands across slate formations, you’re touching stone that predates most life on Earth. Few places in the Midwest give such direct contact with this ancient chapter of geologic history.

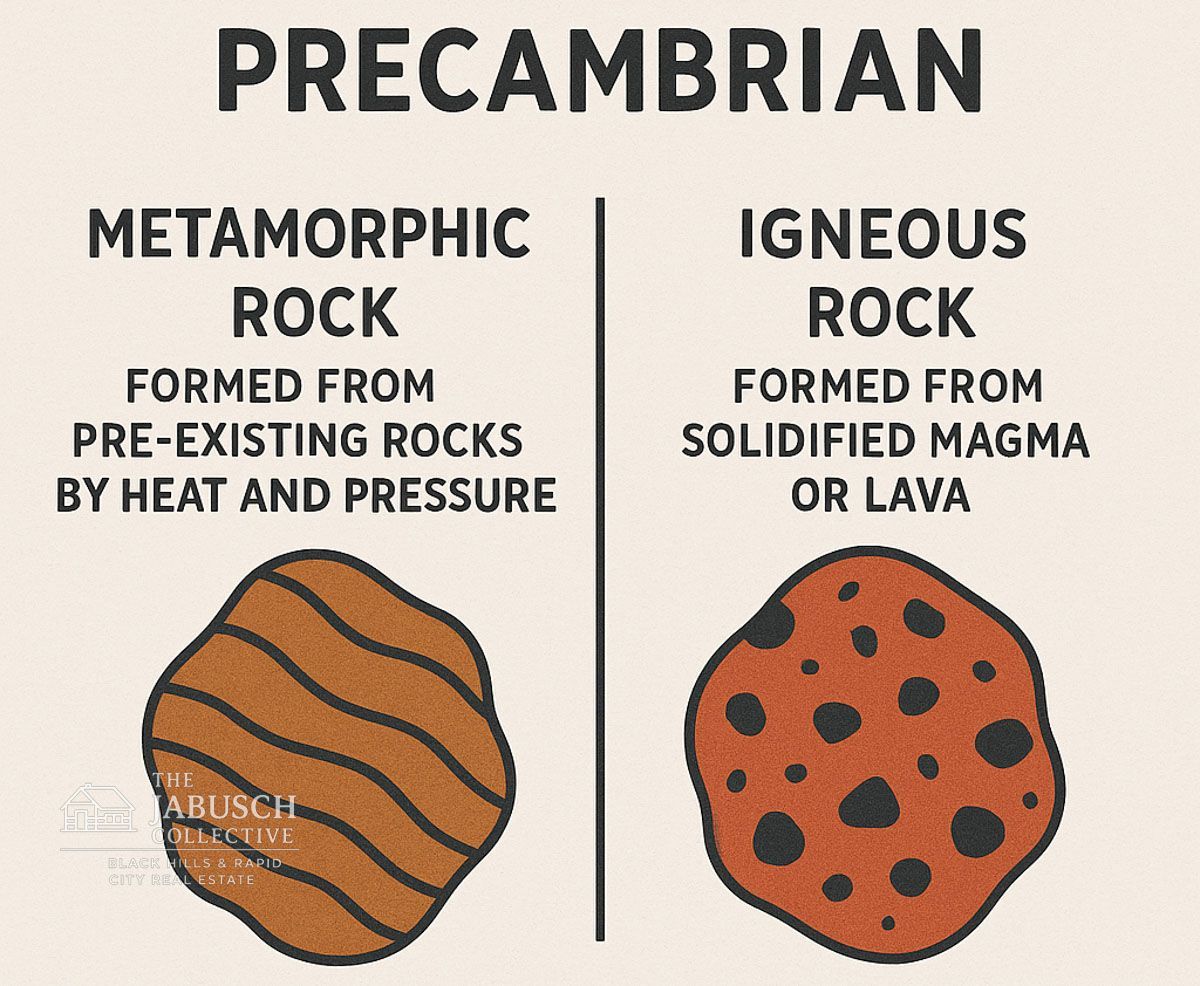

Explaining the Terms: Precambrian, Igneous, and Metamorphic

- Precambrian: A time period before complex plants and animals appeared.

- Igneous rocks (like granite): Formed when molten rock cooled and hardened deep underground.

- Metamorphic rocks (like slate and schist): Originally another type of rock, but transformed by intense heat and pressure.

These rocks became the

foundation of the Black Hills — the solid heart that would later be pushed upward to form the mountains we see today.

A Story You Can Still See Today

Even without a geology degree, visitors notice the uniqueness:

- The smooth pink granite of

Black Elk Peak (the highest point east of the Rockies).

- Glittering

mica flecks in schist that sparkle under sunlight.

- The thin, dark layers of

slate were once part of ancient seabeds.

These features make the Black Hills a kind of outdoor museum — one where every hike and cave tour reveals another piece of Earth’s deep past.

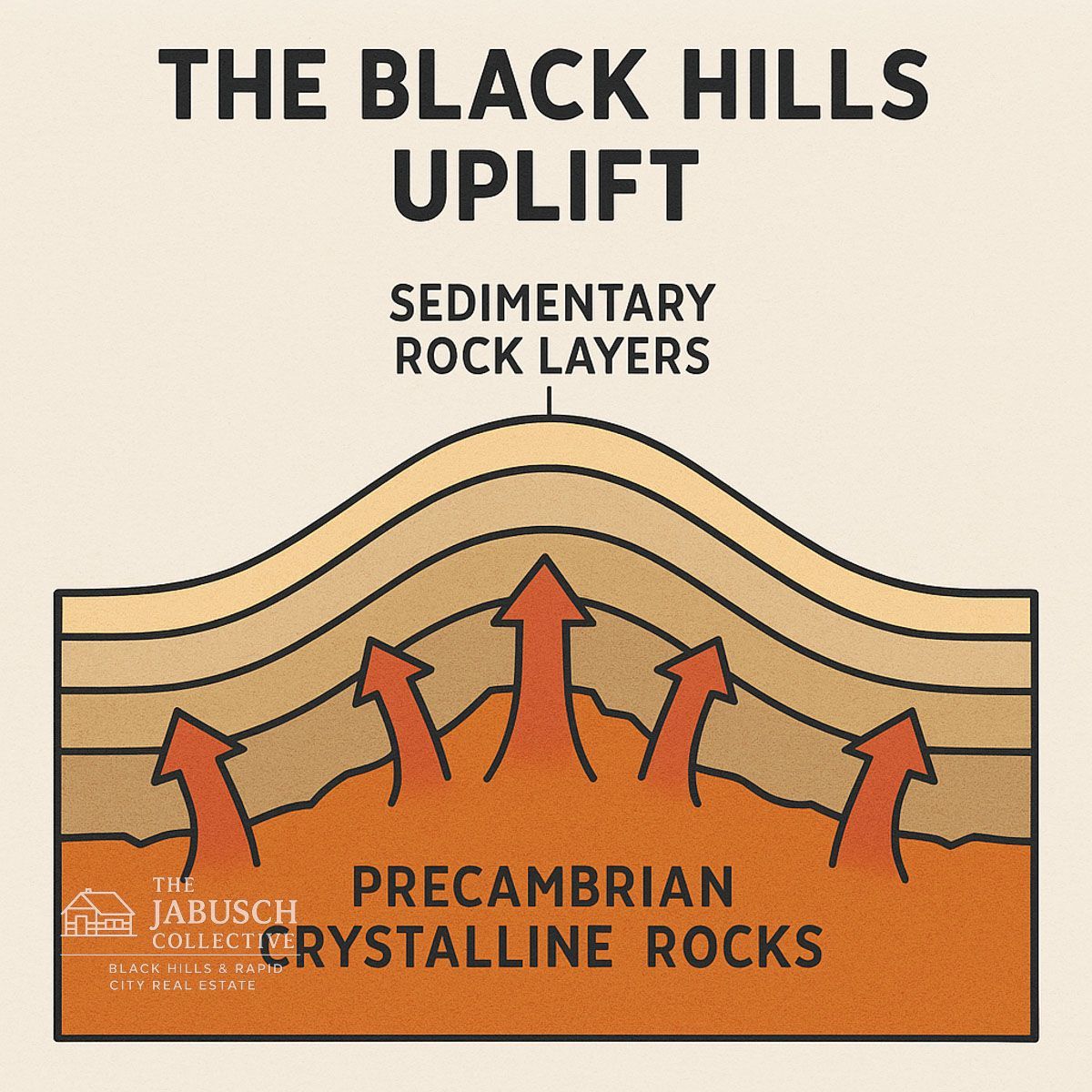

The Black Hills Uplift — How the Mountains Rose

The Black Hills weren’t always towering above the plains. For most of their history, those ancient rocks lay buried under layers of younger sediment. It wasn’t until relatively recently — geologically speaking — that they were pushed skyward.

The Laramide Orogeny: A Mountain-Building Event

Around

65 million years ago, during the same time the Rocky Mountains were rising, a geologic event known as the

Laramide Orogeny reshaped the American West.

- Orogeny simply means “mountain-building event.”

- Instead of creating sharp peaks like the Rockies, the forces here lifted the land in a

dome shape, exposing the ancient rocks at the center.

This uplift is why, today, the oldest rocks (granite and schist) are found in the center of the Black Hills, surrounded by younger sedimentary layers, such as limestone and sandstone.

What Kind of Mountains are The Black Hills?

The Black Hills are classified as

dome mountains. Imagine pushing up on the underside of a blanket — the center bulges while the edges wrinkle. That’s what happened here. The earth’s crust was forced upward in a rounded shape, creating the unique geologic “bullseye” pattern of the Hills.

- Center: Precambrian granite and metamorphic rocks.

- Middle Ring: Sedimentary layers (limestone, shale, sandstone).

- Outer Ring: Younger rocks are still partially intact.

This bullseye pattern can even be seen on geologic maps of the region.

Signs of Uplift You Can See

The Black Hills uplift isn’t just a theory — you can see the evidence while exploring:

- Tilted limestone ridges

near Rapid City show how rock layers were bent upward.

- Granite spires along the Needles Highway reveal the exposed core of the uplift.

- Caves like Wind Cave and Jewel Cave formed in the limestone layers uplifted and fractured by these forces.

In short, the Black Hills rose due to powerful tectonic forces deep underground — forces that have given us the breathtaking landscape millions of visitors enjoy today.

Why Are the Black Hills Called the Black Hills?

The name “Black Hills” doesn’t come from the rocks themselves — it comes from how they look from a distance.

The Lakota Name: Paha Sapa

For the Lakota people, this region has long been sacred. They call it

Paha Sapa, which translates to

“Black Hills.” To them, the dark, pine-covered slopes rising out of the prairie looked like a solid black mass on the horizon.

Pines That Darken the Landscape

Even today, when you approach the Hills from the open plains, the forested slopes appear nearly black against the sky. This visual contrast is striking — expansive golden grasslands suddenly give way to what appears to be a dark wall of mountains.

More Than Just a Name

The name also carries cultural weight. The Black Hills are considered the heart of everything that is, a place of spiritual connection and significance to the Lakota and other Native nations. For modern visitors, the name serves as a reminder that these mountains aren’t just a geological feature — they’re a place with profound cultural and historical significance.

So, Are the Black “Hills” Really Hills?

Despite their name, the Black Hills are much more than hills — they are a small, isolated

mountain range with an ancient geologic story.

Elevation and Relief

- The highest point,

Black Elk Peak, stands at

7,244 feet, making it taller than any summit east of the Rocky Mountains.

- Rising more than 4,000 feet above the surrounding plains, the Black Hills have the vertical relief and rugged terrain that geologists use to define mountains.

Why They’re Called “Hills”

The name comes from a blend of cultures:

- The

Lakota called the region

Paha Sapa (also translated as

He Sapa), meaning

“Black Hills” or

“Black Mountains.” The “black” refers to the dark appearance of the pine-covered slopes when seen from a distance.

- Early

French explorers translated it as

Les Montagnes Noires — “The Black Mountains.”

- Later,

English-speaking settlers adopted the name but used the word “hills,” likely because compared to the towering Rockies just west, these dome-shaped mountains appeared smaller and more rounded.

The Black Hills got their name from the Lakota term Paha Sapa (“Black Mountains”), inspired by the dark pine-covered slopes. French explorers called them Les Montagnes Noires, and later settlers used “hills” since they looked smaller than the Rockies.

Mountains in Everything but Name

While the English name stuck, geologists agree the Black Hills are indeed

mountains — uplifted, eroded, and ancient. Their name may sound modest, but their structure and history tell a far grander story.

Layers of History — Geology You Can See Today

The Black Hills aren’t just ancient in theory — their geology is something you can actually explore. Every cave, ridge, and mining town reveals another chapter in the story of how these mountains formed.

Limestone Caves: Underground Worlds

Two of the most famous caves in the world are found right here:

Wind Cave and

Jewel Cave. Both were carved into the

limestone layers uplifted during the Laramide Orogeny.

- Wind Cave is known for its “boxwork” formations — thin, honeycomb-like calcite fins that are rarely seen elsewhere.

- Jewel Cave earned its name from the glittering crystals that line its walls.

These caves are a perfect example of

karst topography — landscapes where limestone dissolves over time, resulting in the formation of sinkholes, springs, and caverns. On a tour, you’re literally walking through a geologic process millions of years in the making.

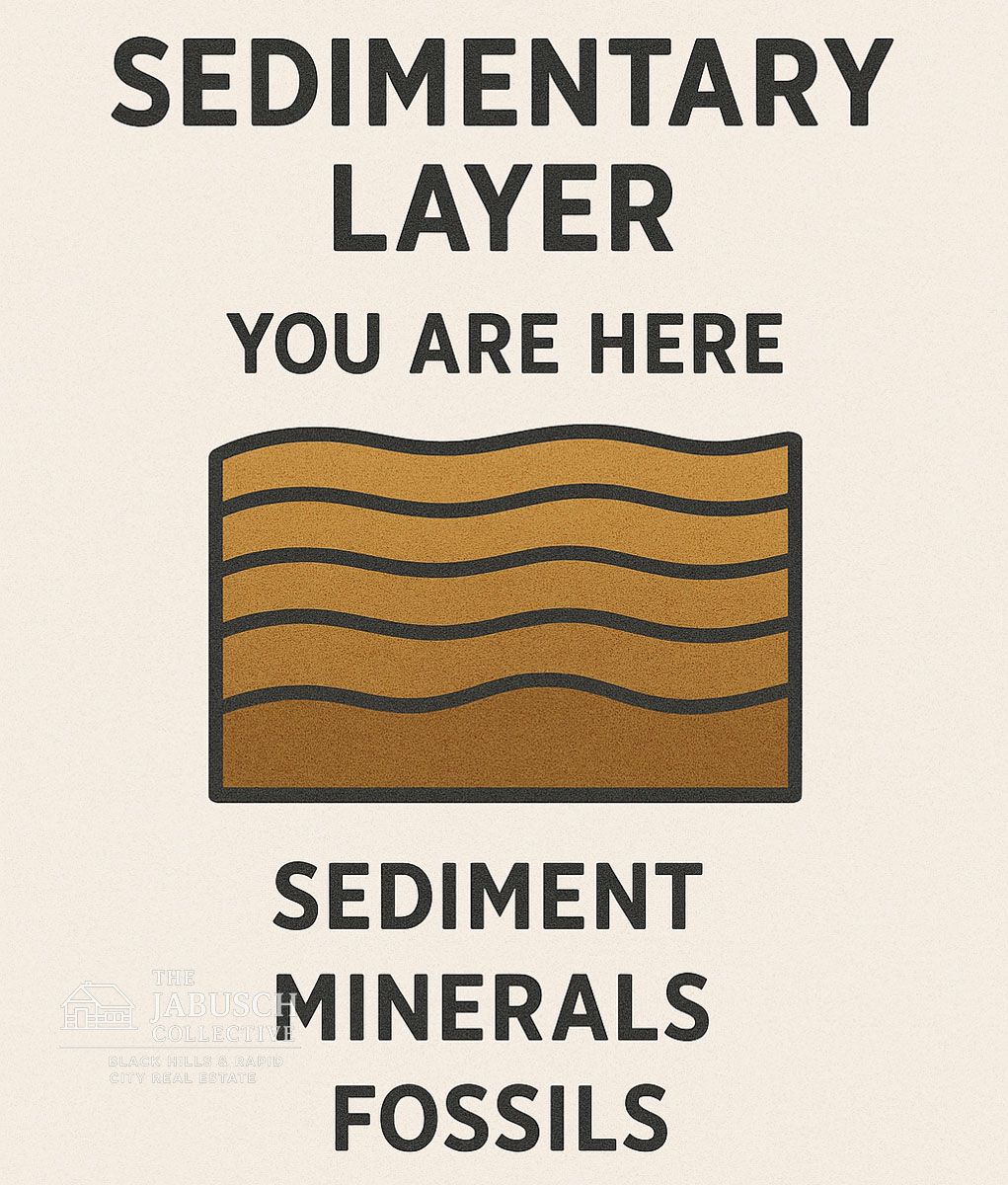

Fossil Evidence of Ancient Seas

Before the uplift, this region was covered by shallow seas. That’s why you can still find

marine fossils — coral, brachiopods, and trilobites — preserved in the limestone and shale layers. Fossil sites across the Hills remind us that what’s now mountain once lay beneath warm, tropical waters.

Gold and the Mining Legacy

The Black Hills are also famous for the

gold rush of 1874–1876, sparked by Custer’s expedition and the discovery of gold near present-day Deadwood. The

Homestake Mine in

Lead

became one of the deepest and most productive gold mines in the Western Hemisphere.

Geologically, the gold formed when hot mineral-rich fluids moved through cracks in the rock, depositing precious metals. Today, abandoned mines and historic towns serve as reminders that the wealth of the Hills is directly tied to its geology.

Slate, Schist, and Granite Peaks

Not all the geology is hidden underground. Hikers and climbers see the variety of rocks firsthand:

- Slate and schist: layered metamorphic rocks that shimmer in the sunlight.

- Granite spires: sharp towers sculpted by weathering, especially along the Needles Highway.

- Black Elk Peak: the granite summit that marks the highest point east of the Rockies.

Each type of rock tells part of the Hills’ story — from fiery origins deep underground to the shaping power of water and wind.

Geology and Today’s Land Use

The Black Hills aren’t just a geologist’s playground — their geology shapes how people live, build, and use the land today. From water access to building foundations, the rocks beneath your feet matter more than most people realize.

Water and Aquifers in the Limestone Layers

Much of the region’s water supply comes from

aquifers stored in the limestone and sandstone layers that ring the Hills. Caves like Wind Cave and Jewel Cave are dramatic examples of how water moves underground in this region. For landowners, this means:

- Wells often tap into these aquifers for fresh water.

- The depth and reliability of wells vary depending on the geologic layer you’re drilling into.

Soil and Agriculture

The geology also influences soil quality.

- Granite-based soils tend to be thin and rocky — better for pine forests than farming.

- Limestone-based soils are richer and can support grazing or small-scale crops. This explains why

ranching thrives in the outer regions of the Hills, while dense forests dominate the core.

Building and Land Stability

If you’ve ever seen a house perched on a granite ridge, you know building here can be both scenic and challenging.

- Steeper, rocky land offers stunning views but requires more planning (and sometimes blasting) for construction.

- Valley and prairie edges offer easier building conditions, but may require attention to drainage and flooding issues.

Mining Legacies

Gold, silver, and other minerals once drew thousands of settlers to this area. While large-scale mining has waned, its legacy persists in abandoned mine shafts, altered landscapes, and even property restrictions in certain regions. Anyone considering land in mining country should be aware of what lies beneath.

Why This Matters for Buyers and Homesteaders

Whether you’re

buying a cabin,

planning a homestead, or investing in land, understanding the Black Hills geology isn’t just trivia — it’s practical.

- A well’s depth, water flow, and quality often depend on which rock layer you’re tapping.

- Soil types can determine whether your land is ideal for gardening, grazing, or forestry.

- The dramatic terrain that makes the Black Hills so beautiful can also shape what kind of foundation, access roads, and utilities you’ll need.

If you’re considering

purchasing land in the Black Hills, it’s worth pairing your dream with a bit of geologic know-how. At

Jabusch Realty, we help clients navigate not just the market, but the land itself — making sure your property fits both your vision and the realities of the Hills.

Conclusion

The Black Hills are more than just a scenic backdrop — they are a

living record of Earth’s history. From billion-year-old granite spires to limestone caves carved by water, every layer tells a story. Their rise during the

Black Hills uplift shaped not only the mountains we see today but also the land we live on, hike across, and build our homes upon.

We’ve seen how the Black Hills are truly

mountains in every sense — uplifted, eroded, and ancient — despite their modest name. We’ve explored why they appear so dark from a distance, why caves and fossils reveal secrets of ancient seas, and how gold and other minerals once drew people from around the world. And we’ve connected it all to today, where geology still determines the availability of water, soil, and the way land can be used.

Whether you’re a traveler marveling at the

granite peaks of Black Elk Peak, a hiker venturing into

Wind Cave’s boxwork passages, or a future landowner hoping to plant roots in this storied region, understanding the geology of the Black Hills helps you see them for what they really are: a landscape of resilience, beauty, and history written in stone.